[ad_1]

In Shinjuku, just west of the world’s busiest train station, the colossal towers of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building hover above a mass of skyscrapers. The cathedral-esque facade was designed by architect Tange Kenzo to resemble an integrated circuit; what better symbol could there be for Tokyo, a metropolis whose meteoric rise was predicated on high tech? The whole of Tokyo and its byzantine bureaucracy is governed from within this massive complex. And presiding over it all, and over more than 150 thousand local government employees, is the Governor of Tokyo.

As the head of government for Japan’s capital – the world’s most populous urban area with its greatest single GPD – the governor of Tokyo is a uniquely powerful entity on both a local and national scale. Since 2016, the office has been occupied by Koike Yuriko, a conservative nationalist and Tokyo’s first female governor. That Koike would be a conservative (and at times even labeled an “ultraconservative”) likely comes as no surprise; Japan’s national government has been controlled by the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party for the vast majority of the country’s post-war history. That Japan’s local governments would also be similarly led by conservative politicians is a rational assumption; indeed, most Tokyo governors have been conservative, or even arch-conservative. But this wasn’t always the case.

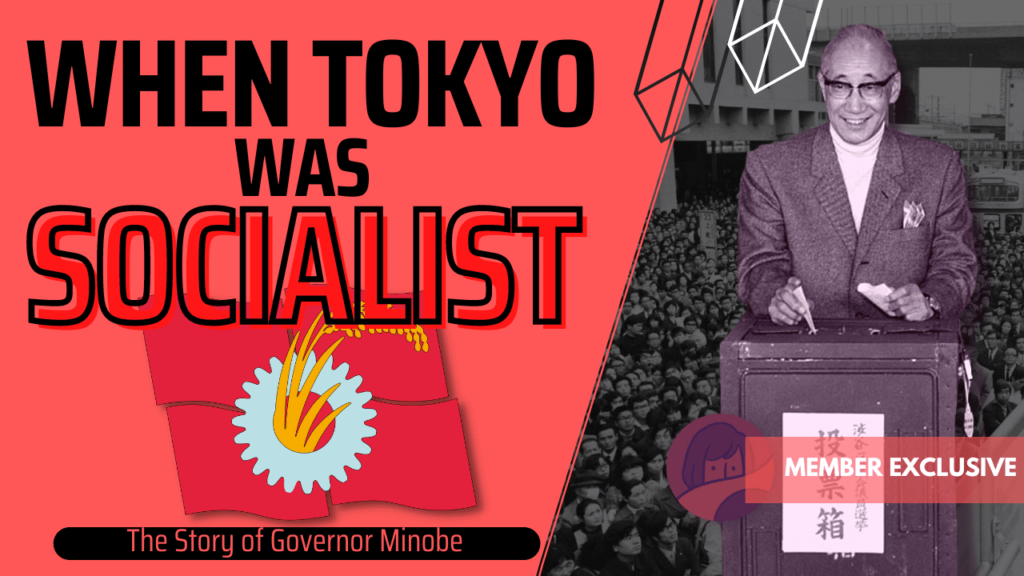

In the late 1960s, there emerged a major upswell in local support for progressive politicians. Across Japan, nominees backed by the Japanese Socialist and Japanese Communist parties found themselves newly empowered. Prefecture after prefecture chose left-wing leadership, eschewing the hand-picked nominees of the ruling LDP. And chief among these radical local leaders was Minobe Ryokichi, a Marxist professor, smiling TV star, and the son of a wartime enemy of the state. Minobe would lead Tokyo for three terms, remaining electorally undefeated upon leaving the post in 1979.

For more than a decade following his election in 1967, while Minobe Ryokichi led Japan’s capital from the old government building in central Chiyoda, Tokyo launched a series of groundbreaking progressive policies aimed at increasing quality-of-life for the metropolis’ millions of citizens. And, for a time, one could almost say that Tokyo was socialist.

Born into an Era of Change

Minobe Ryokichi (美濃部亮吉) was born in 1904, the 37th year of the Meiji era. Three days after his birth, the Russo-Japanese War began; by the time Minobe passed away in 1984, Japan was an ascendant economic giant long since recovered from the devastation of WWII. His birthplace was the capital of the Empire of Japan, although Tokyo had not yet taken the administrative form he would eventually govern. At the time, it was known as Tokyo-fu – the Tokyo Metropolitan Prefecture. There was even still such thing as a “Tokyo City,” then composed of a mere 15 wards, its boundaries falling far short of the 23 special wards we know today.

Minobe grew up in a rapidly changing Japan, one which had emerged from its feudal isolation to become an industrializing world power. When he was ten years old, Emperor Meiji passed away. Minobe’s adolescence occurred during the comparatively open and forward-thinking years of the so-called “Taisho democracy,” wherein Meiji’s son and heir, the Taisho emperor, was too frail to effectively project the power of a monarchic state. Minobe’s own father, Tatsukichi (美濃部 達吉), was one of the great constitutional thinkers of the age.

Father’s Theories

The elder Minobe was a professor at Tokyo Imperial University. In 1912, the year of the Meiji emperor’s passing, he published his writings on what would become known as the “emperor organ theory” of state. To Minobe Tatsukichi, the constitution of Japan clarified the emperor’s position within the state as being one organ among many; the emperor had an important role to play alongside the various levers of government and bureaucracy. Together, all the “organs” of state comprised the kokutai (国体)- the national polity. For many liberal thinkers of the day, this was a fitting explanation of the emperor’s place in civic society, and one which paved a path toward Japan’s function as a constitutional monarchy.

While the Taisho emperor yet reigned, the organ theory easily held water. After all, the emperor was not physically able to rule, and could hardly impose his will over the decisions of the government. All the while, however, Taisho’s son, Hirohito, was being raised to occupy a position more like that of his powerful grandfather Meiji than his rarely-seen father. Hirohito read the elder Minobe’s theories, but generally rejected them for oppositional constitutional readings that would grant him greater power. Once Hirohito was enthroned as the Showa emperor in 1926, he quickly developed a much stronger cult of emperor worship than his father – one which would eventually become more fanatical than even that devoted to Meiji. In the increasingly bellicose 1930s, far-right radicals began targeting Minobe Tatsukichi, decrying his “organ theory” as blasphemy against the all-encompassing power of the emperor.

Minobe Ryokichi watched on as his father went from celebrated pioneer of constitutional thought to persona-non-grata. In the early 1920s, the younger Minobe entered the prestigious economics department of the Tokyo Imperial University – the very school where his father was director of the Faculty of Law. He was quickly taken under the wing of the influential Marxist economist Ōuchi Hyōei (大内 兵衛). Via Ōuchi, Minobe would be introduced to the Rōnō-ha (労農派, labor-farmer) school of Marxist thought. In the 1920s, Communist professors could still operate with comparative freedom within Japan – yet Ōuchi had already faced governmental scrutiny for his views. In 1919, the Home Ministry had taken him to court over his assistance in the publication of an academic article the government deemed “anarchistic.” The Russian Revolution had only just occurred; even within the lax environment of the Taisho era, the power structure feared that leftist radicalism spread to Japan.

The Targeting of Minobe and Son

Despite the increasing difficulties both Ōuchi and the younger Minobe would face during the pre-war years, the teacher and pupil remained close. Even into Minobe’s third term as governor in the then far-off 1970s, he would still turn to his old instructor for advice. Back in the 1920s, Ōuchi set Minobe down an academic path focused on the issues Marxism predicted for late-stage capitalism; his specialty became inflation.

In 1927, Minobe graduated, immediately taking on a job as an assistant professor at his alma mater. Soon made a full professor, his matter-of-fact belief in the compatibility of being both a Marxist and an everyday member of society soon brought down the wrath of the anti-communist professor Kawai Eijiro. Life at Tokyo Imperial became untenable for Minobe just as his father’s public life was coming under repeated attack from far-right forces. (Kawai, a firm believer in Democracy, would eventually face his own sustained attack from the right.)

On February 18th, 1935, the radical rightist Baron Kikuchi Takeo took to the House of Peers to publically decry Minobe’s father’s “organ theory.” The theory, the Baron insisted, was “the traitorous thought of an academic rebel.” The Baron called upon the government of Prime Minister Okada to ban Tatsukichi’s writings. The Baron was a retired Imperil Army general; the army was becoming ever more bellicose and unruly, taking action on the Asian mainland and countermanding the Japanese government. Radicals throughout the army wanted to enact a “Showa Restoration,” granting the Emperor unlimited power. Tatsukichi’s theories stood in the way, and he became the target of mass rage.

Son to a Persona non Grata

A week after the Baron’s speech, Tatsukichi gave an impassioned defense of his theories in front of the House of Peers (of which he was himself a member). Outside, protesters aligned with the Imperial Way faction held placards denouncing Minobe as a traitor. Prime Minister Okada bowed to rightist pressure, banning Minobe Tatsukichi’s work and allowing him to be investigated for the crime of Lèse-majesté (insulting the monarch). Minobe stepped down from his imperial appointments; the government began a process of spreading the “correct” conception of the emperor’s place in society.

The banning of Minobe’s father’s books and his retirement from public life did not entirely satiate the anger that had been drummed up against him. On February 21st, 1936, a far-right hoodlum named Oda Juzo (小田十壮) used a falsified business card to gain a meeting at Minobe’s house. Inside a gift basket, he hid a pistol; after exchanging pleasantries with Minobe, he pulled the gun, and unloaded at the older man. Minobe was hit, but managed to flee; he caught his leg up in barbed wire as he ran across the fields near his house. Although badly wounded, the elder Minobe survived the assassination attempt. Oda received only three years imprisonment as punishment. [1]

Only two years would pass from the attempt on his father’s life until Minobe himself was imprisoned. Starting in 1937, with the fall of Nanjing, the Japanese police began making regular mass arrests of known leftists. In 1938, the police came for Minobe, briefly imprisoning him because of his association with the Rōnō-ha group. Minobe’s mentor, Ōuchi, was arrested the next year. Both were fired from their universities and had to look for work elsewhere. The watchful eyes of the Japanese secret police maintained their secretive gaze on the Minobe family until the fall of the Empire of Japan in 1945.

Despite all he had experienced, all the terrible things he had seen happen to those close to him, Minobe Ryokichi emerged through the utter devastation of the war years relatively unscathed. Perhaps because of the percecution he’d experienced, he held firm to his Marxist beliefs – even in his later years as a politician, when many leftists began to doubt his commitment to the revolutionary cause, he’s still call himself a “flexible utopian Socialist.” With the old system in ruins and the US occupation opening up politics to all creeds and backgrounds, the sky seemed the limit for what could be achieved in Japan.

Emerging into the Post-War

Tokyo emerged from World War II as a burnt-out husk of its former self. No longer the capital of one of the largest empires on Earth, it was now merely a city of rubble from which a foreign occupying power ruled. Minobe witnessed the many years of US occupation and rebuilding as both an editorial author for the Mainichi Newspaper, and as a high-ranking statistician for the disempowered government of Japan. Meanwhile, his father, Tatsukichi, became an active advisor in the compilation of Japan’s new post-war constitution. He would pass away in 1948.

1947 saw a major change in the composition of Tokyo itself. The 23 special wards system came into effect; the borders of what had been the City of Tokyo were extended into what was once the countryside (including such major modern population centers as Shinjuku and Shibuya). Meanwhile, the very first popularly elected governor of Tokyo, Seiichiro Yasui, came into power, presiding over both the 23 special wards of the old City of Tokyo and the municipalities that lay beyond in Tokyo’s western boundaries.

The Occupation years were a time of great poverty, difficulty, and malaise, but also of innovation. Unburdened by the oppressive levers of the Imperial State, labor unions and alternative political parties flourished. A true popular vote, including the long-awaited enfranchisement of women, came into effect. Obtaining a liberal education became a goal of many young people, even though the university infrastructure would take years to repair itself and catch up with demand. Socialist and Communist party members, released from imperial prisons, emerged as folk heroes. The Japanese Socialist Party gained in popularity, and through the early 50s proved a powerful force in electoral politics.

The Rise of the LDP

Meanwhile, as the dangers of the Cold War became apparent, and in light of both the threat of the Soviet Union and the victory of the Communist army in the Chinese Civil War, the Occupation forces did an about-face. The United States felt that the desire for a democratic society had been instilled in the Japanese populace, and it was now time to shore up Japan as a bulwark against communism, rather than letting the country move farther to the left. The CIA began secretly funneling money to the various Japanese right-wing parties; in 1955, the conservative side of Japanese politics coalesced from warring factions into a single, powerful party – the Liberal Democratic Party. The Socialist Party could no longer count on competition from within the conservative wing to allow them to eke out victory. From 1955 until 1993, the LDP easily held the reigns of government, and for decades did so with the illicit support of the CIA. [2]

Meanwhile, said US intelligence agency infiltrated “the opposition,” meaning the Socialists, Communists, labor movements, and the burgeoning Leftist student movements. One CIA agent would later remark that preventing gains by Japanese leftists “was the most important thing we could do.” CIA agents believed the Soviet Union was similarly funding the Japanese opposition; the US used the domino theory of geopolitics to push the belief that if Japan went red, so would the whole of Asia. Douglas MacArthur II, nephew of the leader of the US occupation and ambassador to Japan from 1957 to 1961, said that:

“If Japan went Communist it was difficult to see how the rest of Asia would not follow suit. Japan assumed an importance of extraordinary magnitude because there was no other place in Asia from which to project American power.”

The US strategy worked; in the face of a unified and financially stable conservative front, progress made by leftist and liberal candidates on both a national and a local stage was rolled back. The LDP shored up Japan’s postwar relationship with the US, and made sure the numerous US bases throughout the archipelago remained in operation despite local opposition. For a decade, Leftism in Japan became the purview of student radicals, activists, and labor unions whose power was often in the streets, rather than the halls of government.

The Japanese Radical Youth Take to the Street

In 1960, hundreds of thousands of protesters who opposed the United States–Japan Security Treaty surrounded said halls of government in Tokyo’s National Diet Building. On June 15, the protesters breached the walls of the Diet compound. A pitched battle with riot police followed. One female student, Kanba Michiko, perished. A visit from President Eisenhower was canceled, and LDP Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke – formerly imprisoned as a class-A war criminal suspect (and grandfather to recently slain former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo) – stepped down from his office. Progressive and liberal forces within Japan still had mass support and organizing power, but electoral politics remained beyond them.

(One major exception was Governor Ninagawa of Kyoto, elected in 1950 with Socialist backing. He remained governor of one of Japan’s major prefectures for 27 years despite opposition from the conservative parties. Ninagawa is still by far the longest-serving governor in Kyoto history.)

Minobe on TV

It was in 1960 that Minobe Ryokichi entered into public awareness. Having worked in numerous professorial and advisory offices, it was becoming a television personality that truly made him a household name. Minobe starred in the NHK program “Yasashii Keizaikyoshitsu” (やさしい経済教室, “The Easy Economics Classroom”). He played the “father” of a fictional version of the “Minobe Family,” with Mizuki Ranko playing his wife. Sitting on the living room tatami, Minobe would explicate economic issues to his fictional family in easy-to-understand ways. The show touched on such subjects as Minobe’s specialty, inflation, and also explained kitchen economics and Japan’s changing place in the world economy. The show ran for two years, and Minobe’s gentle, fatherly smile became beloved across the country.

Tokyo in Recovery

The Tokyo of the early post-war decades was not one we’d recognize today. Much reconstruction had been achieved, but there remained massive issues with local infrastructure and poverty. Hardly anyone in the 23 wards had access to sewers; night soil haulers operated in some ways as they had since the days of Edo. Neither Tokyo nor Japan as a whole had really stepped back into the so-called “brotherhood of nations.” A plan was hatched to use the Olympics as a venue through which to reintroduce the world to the new, peaceful Japan. One of the men behind these efforts was Azuma Ryutaro, the head of the Japanese Olympic Committee. In 1959, he was elected as the second post-war governor of Tokyo – in the words of Edward Seidensticker, “as if for the specific purpose of presiding over” the Olympics. That same year, Tokyo won its bid to host the 1964 summer Olympics, and the prefectural government dove headfirst into making Tokyo ready for this monumental task.

During the ramp-up to the Olympics, Japan saw the first hint that left-wing nominees would soon regain a fighting chance with the electorate. In 1963, Asukata Ichio was elected as mayor of Yokohama, one of Japan’s most important cities. Asukata was the founder of the National Association of Progressive Mayors, whose goal was to elect local-level progressive politicians who would campaign on promises of increasing quality of life.

Asukata’s electoral coup, however, mostly served to demonstrate the great difficulty progressive politicians would have upon assuming executive offices. Socialists and communists could compete in mayoral and gubernatorial elections because these were first-past-the-post style competitions, unlike those for the apportioned National Diet. Once a progressive politician gained such an office, however, they still had to deal with the city and prefectural councils and organs beneath them, usually filled with members associated with the ruling LDP. According to Mayor Asukata, becoming mayor amidst the entrenched conservative governmental structure of Yokohama was like “landing alone on the top of Mt. Fuji by parachute: I occupied only the summit, while the whole of the mountain was in the hands of the enemy.”

Asukata’s time as mayor would still see some success, and presaged the oncoming rush of local progressive leadership. The mood of the nation had changed in the 1960s; while the Olympics are remembered as an epochal moment for post-war Japan, the country would shortly be rocked by a series of scandals, all while the youth became increasingly aligned with the Left. (Indeed, the youthful New Left movement was radicalized to such a degree that they broke with the Communist Party, seen as too moderate.) Scandal would also come for Tokyo’s “Olympic governor,” Azuma, and leave the door open for an opposition candidate to eke out victory in the coming elections.

Bribery and corruption have long been open secrets within the political landscape of Japan; only at times do scandals erupt to a great enough scale to bring down those involved. In 1965, the year after the Olympics, the Tokyo Prefectural Council held an election for their president in which the degree of bribery and intimidation involved was such that it slipped the bonds of everyday corruption and entered public discussion. The prefectural president himself was arrested, among others, and the council dissolved. This in of itself was enough to put a great dampener on the perception of Governor Azuma. It was then that an almost literal Biblical plague of flies descended upon Tokyo.

The Tokyo Garbage Wars

Tokyo had a monster-sized trash problem.

Since 1655, in the early Edo era, the city’s garbage had been disposed of via reclamation in Edo Bay. The area that is now Tokyo’s Koto Ward rose from the sea as the Shogunate used trash to form land extensions and islands. Edo was at various times the most populated city in the world; however, it was only from the 1950s and the rise of mass-produced consumer goods that trash became a crisis. The civic battles between different Tokyo wards – those wishing to dispose of their trash elsewhere, and those refusing to take on said trash – became known as the Tokyo Gomi Sensou (東京ゴミ戦争) – the Tokyo Garbage Wars. (A name Minobe himself would coin.)

Under Prime Minister Sato’s Income-Doubling Policy, Japan was moving into a state of rapid industrialization, and the disposal of industrial materials, dangerous chemicals, and the increased output of pollution all combined to create serious public hygiene issues. Landfills in the various wards filled up. Incineration stations remained few and far between. The main method of disposing of garbage returned to landfills in Tokyo Bay, and the continuous reclamation of land from the sea. The amount of trash was so massive that garbage plants couldn’t even begin to handle the load; 70% was buried without being treated.

From 1957, the focal point for the disposal of Tokyo’s massive wave of trash became the ironically named Yume no Shima – the “Island of Dreams.” Itself a man-made island in Tokyo Bay, by 1965 the island had already seen a mass trash fire rage across 40% of the island’s surface. The Japanese media took to calling the island by a derisive name: Gomi no Shima – the “Island of Trash.”

Plague of Flies from the Island of Dreams

Then, in 1965, the problems at Yume no Shima began to truly plague the whole of Tokyo. It began on July 16th. An enormous mass of black flies, born from and engorged on the island’s trash, road a strong southern wind towards the Koto Ward mainland. From there, they unleashed a blight upon the people of Tokyo. They were everywhere. Students at elementary schools near the swarm had to carry out fly-killing exercises between classes. Young children were outfitted with fly swatters to wield on walks to and from school.

Efforts by the police and Self-Defence Force at fly eradication only made matters worse. Finally, the fire brigades and the Self-Defense Force united to carry out “Operation Yumenoshima Scorched Earth.” (夢の島焦土作戦.) They spread chemicals and gasoline over the entirety of the garbage mounds from which the flies were emanating; then, they lit a match. Witnesses described an otherworldly scene, as a fire “firefighters who had devoted their lives to putting out flames engaged in arson…” creating a blaze like “a nightmare in the middle of the day.” [3] According to Edward Seidensticker, “dream island was for a time a cinder on which not even flies could live.” In 1967, the local government declared that Yumenoshima would officially cease its operations as a trash dump.

Scandals, public unrest, and a biblical plague of flies all united to bring down the LDP’s stranglehold on Tokyo government. The 1965 Prefectural Council elections were a media circus; indicted former councilors ran for re-election while awaiting their trial dates; numerous yakuza attempted to run for council seats. The conservative wing lost almost half of its seats, and the socialist wing emerged as the leading party in a new coalition. Conservative majority power in Tokyo was broken for decades to come. Governor Azuma chose not to run for re-election – and the path was opened for an even greater socialist sweep.

[ad_2]

Source link