[ad_1]

On January 1st, the entire world welcomes the start of the new year. Different countries have different customs and traditions. But one country that stands out is Japan, with its culture-rich New Year’s traditions.

Japan’s New Year’s celebration is known as the Oshogatsu. It is a series of festivals focusing on worshiping the Shinto god Toshigami (literally God of Years). The Japanese New Year’s season is also the perfect opportunity for families to reunite, with parents and adults giving gifts to children, and individuals showing gratitude to their friends and colleagues.

Oshougatsu is a celebration that the Japanese deeply respect and carry out yearly. However, it is also a tradition that allows everyone to relax, have fun, and positively welcome the coming year.

And while the Oshogatsu celebrations are primarily meant for Japanese people, they can also be experienced by foreigners visiting Japan. There are activities that visitors can take part in and merchandise that they can purchase.

Have you signed up to ZenMarket yet?

In this article, we will be learning more about Japan’s New Year Celebrations. We will discuss the celebration’s origins, traditions, activities during Oshogatsu, the merchandise you can buy, and Japanese New Year phrases.

What is Oshogatsu?

Oshogatsu (お正月) is Japan’s version of the New Year’s celebration. However, unlike other Japanese celebrations near the end of the year, such as Japanese Halloween and Christmas, Japan’s New Year Celebration is not an imported event.

Also Read: ULTIMATE GUIDE TO HALLOWEEN IN JAPAN

Also Read: ULTIMATE GUIDE TO CHRISTMAS IN JAPAN

While it takes place at the same time as the rest of the world’s New Year’s celebrations, Oshogatsu is a distinctly Japanese celebration with many unique ancient Japanese traditions that have been practiced for hundreds of years.

For instance, Japan does not usually celebrate Oshougatsu by having large fireworks displays at midnight on January first. Instead, the Japanese conduct several traditions to honor the gods and show gratitude towards families, friends, colleagues, etc.

Also, unlike adopted celebrations mostly meant for fun, Japanese people take Oshogatsu seriously as they believe it is the time for purification and renewal.

Another distinct feature of Japan’s Oshogatsu is that the celebrations honor the Shinto Kami (god), Toshigami-sama. The Japanese believe that Toshigami-sama visits their homes to bring good luck and fortune for the coming year.

Therefore, it is only right that the Japanese honor him through their celebrations and decorations. Toshigami-sama is also known as the god of grain. The Japanese worshiped him during ancient times to bring a good harvest.

The Oshogatsu festival isn’t just a single event that concludes within a day. It is a series of festivals and activities that occurs in three days.

When do Japanese people Celebrate New Year?

Japan’s Year-end celebration takes place on January first. The Japanese term for New Year’s Day is “Gantan” (元旦).

Unlike the New Year’s celebrations in most countries, Japan’s Oshogatsu lasts for three days and ends on January 4th.

Oshogatsu has been celebrated annually on this date since 1873 when the Japanese adopted the Gregorian calendar. Before 1873, the Japanese celebrated New Year based on the lunar cycles.

Japanese New Year decorations can be placed as early as December 13th. However, they are usually placed after Christmas (December 25th).

Also Read: ULTIMATE GUIDE TO CHRISTMAS IN JAPAN

With that said, the Japanese avoid two specific dates for decorating their homes. The first date is December 29th. In Japanese, 29 is read as “Nijūkyū” (二十九). However, that word is a homonym for “Ni Juku” (二重苦), which means “pain and suffering” or “double hardship.”

Given the negative connotation of the date, the Japanese believe it is best not to decorate their homes on this day, especially since they are asking for success and prosperity for the coming year.

For many Japanese people, December 28th will generally be the last working day of the year, with the New Year’s holiday starting on December 29th, to avoid work being completed on this day.

Also Read: THE IMPACT OF JAPAN’S NEW YEAR HOLIDAYS ON ZENMARKET ORDERS

The other date that the Japanese avoid is December 31st. For them, not preparing in advance is considered rude and disrespectful to Toshigami-sama. Just another quirk of Japanese hospitality (Omotenashi).

Once the New Year Celebrations have ended, New Year decorations are removed and burned at specific areas such as shrines. The act of burning the New Year decorations serves as a sendoff to Toshigami-sama to safely return to the heavens.

In the Kansai Region, they burn decorations on January 15. In other areas, the burning of decorations is held on January 7.

Do you have a ZenMarket account?

How is the Japanese New Year Celebrated?

Unlike Christmas, which couples and groups of friends casually celebrate, the Japanese New Year is celebrated with family and close relatives. During the end of the year, families gather and spend time together to show their gratitude towards each other and to honor and worship Toshigami-sama.

Also Read: ULTIMATE GUIDE TO CHRISTMAS IN JAPAN

Also, during the Japanese New Year, several traditions are conducted. Japanese houses are decorated with items made up of specific materials that have a deeper meaning. The tradition of sending postcards to each other is also observed.

Money and gifts are also given to children. And most importantly, families spend Oshogatsu visiting temples and showing their gratitude towards the gods.

Japanese New Year/Oshogatsu Traditions

Japanese New Year Decorations

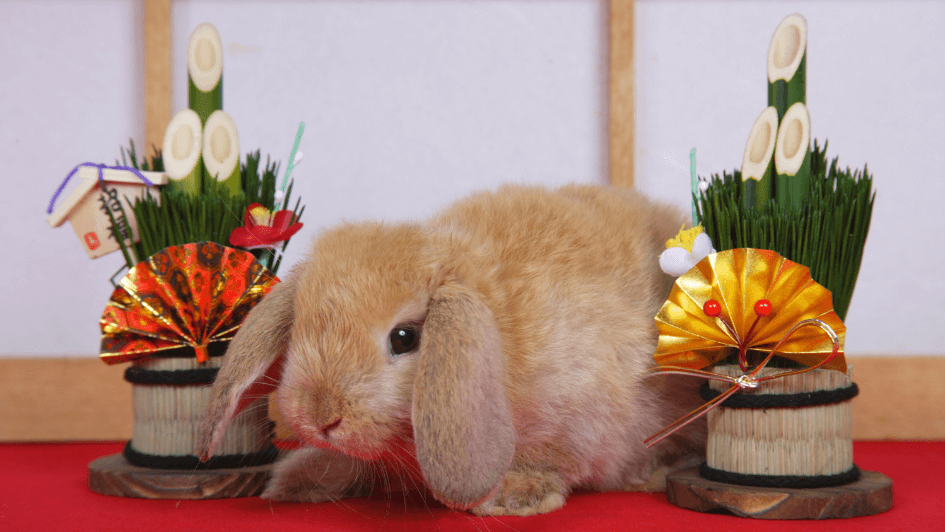

The Japanese New Year’s first major tradition is decorating houses with items that honor Toshigami-sama. Three items are found in every household during the New Year season. These are the “Kadomatsu” or gate pine (門松), Shimekazari (注連飾), and the “Kagami Mochi” or mirror rice cake (鏡餅).

The Kadomatsu is a Japanese decoration made of pines and bamboo. It is a landmark that lets Toshigami-sama know the location of your home. The Kadomatsu is made with pines and bamboo because pines symbolize vitality, as they do not lose their green color even during the winter.

Also, the fact that pines grow fast symbolizes longevity and prosperity. The Kadomatsu is meant to be placed outside on the front door of Japanese homes. But in modern times, the Kadomatsu has been relocated inside Japanese houses to avoid bothering others and to comply with apartment rules and regulations.

Because full size kadomatsu are big and bulky and unlikely to fit nicely into most Japanese homes, smaller more ornate versions have become popular (rabbit included for size reference and additional cuteness). They are often small enough to be given as gifts.

The Shimekazari acts as a barrier that separates the human world from the sacred world of the gods. This decoration symbolizes a gateway that allows Toshigami-sama to safely enter our world.

This decoration is placed on the front door of Japanese houses, kind of like a Christmas wreath! But just like the Kadomatsu, the Shimekazari can be placed indoors to fit the rules of modern Japanese society. Shimekazari however must specifically be placed at a high location to properly serve its purpose as a barrier

Lastly, the Kagamimochi is a Japanese food that serves as an offering to Toshigami-sama. As its name implies, the Kagamimochi is primarily made of “mochi,” which ancient Japanese people considered a sacred food.

Since mochi is made with rice grains and Toshigami-sama is the god of grain, mochi naturally became a food that was considered a gift from the gods.

Unlike the previous two decorations, the Kagamimochi isn’t traditionally placed in front of a Japanese house. Instead, it must be placed on a sheet of Japanese calligraphy paper and the house’s shrine or the “tokonoma” in the guest room of Japanese houses.

Of course, since modern Japanese houses and apartments don’t always have these areas, the Kagamimochi can also be placed on a regular table inside the house. After the New Year’s celebrations, families eat the Kagamimochi to receive the blessing of Toshigami-sama.

Kagamimochi can be found readily available at almost every supermarket in Japan between Christmas and New Year’s.

Japanese Envelopes/Postcards

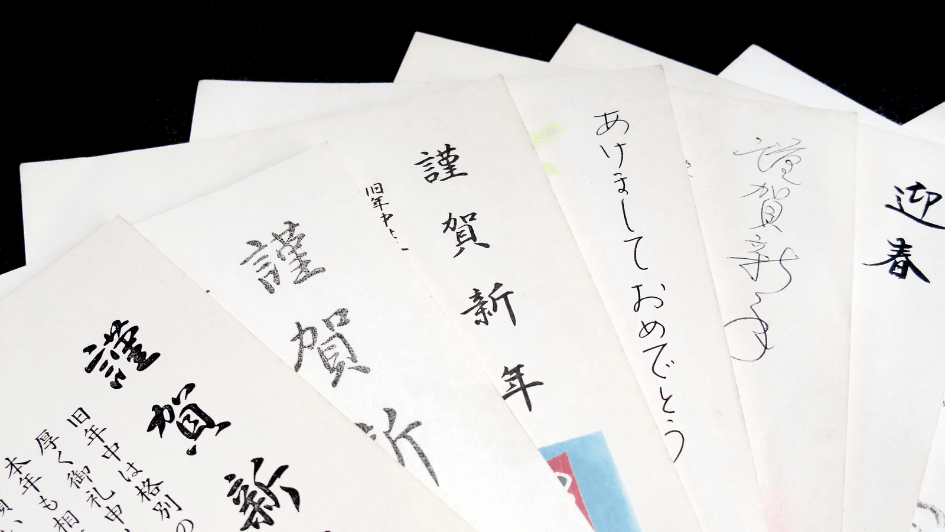

Another major tradition during the Japanese New Year is giving postcards called “Nengajyo” (年賀状). The purpose of sending these postcards is to formally greet your friends and acquaintances. It is similar to the western tradition of sending Christmas cards.

In the past, the Japanese people visited each other’s homes to personally greet them. However, since many Japanese homes are far from each other, personally visiting other people is quite difficult.

During the Heian era (794-1185), the nobility started writing letters to greet friends and family who lived in farther places. Once the Japanese postal service took off and started creating postcards in 1871, the Nengajyo tradition was born.

The Nengajyo usually contains the Japanese phrase “Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu,” which means Happy New Year, and “Kotoshi mo Yoroshiku Onegaishimasu” which roughly translates to “Thank you for all your support for this year in advance” or “looking forward to our continued relationship.”

In addition, Japanese people tend to send personal messages, such as their New Year’s resolutions along with their family photos. The Nengajyo can be sent to friends, relatives, colleagues, and anyone who has helped you throughout the year.

However, Nengajyo should not be sent to someone who has lost a family member during the year. These people send mourning postcards called “mochuu hagaki” (喪中はがき) to let others know that they will not be celebrating the New Year.

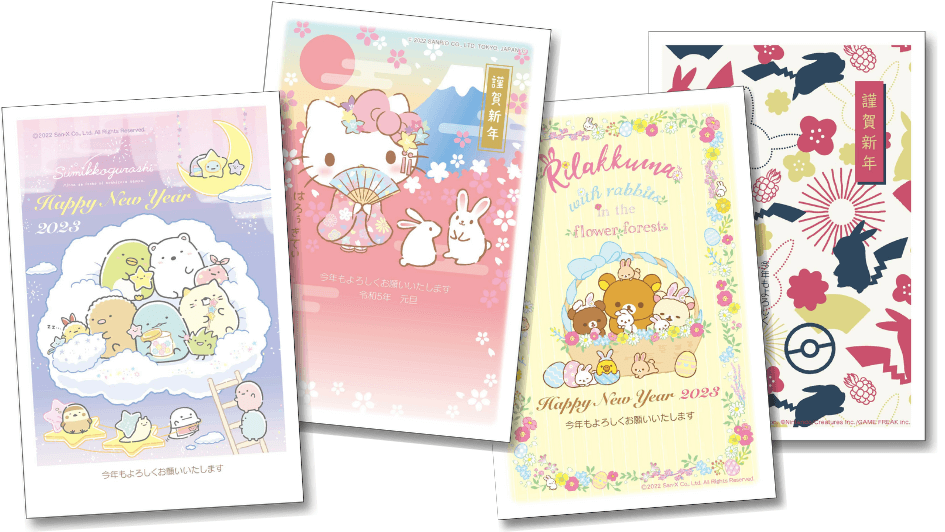

The Nengajyo are usually written and sent between December 15th and December 25th to ensure that the recipients will receive it during the New Year. Also, due to how long the Nengajyo tradition has been around, plenty of postcard designs are sold during the New Year season. Find Japanese New Year’s post cards with characters such as Doraemon, Snoopy, Hello Kitty, Pokemon, Sumikko Gurashi, Sanrio characters and more.

Of course, individuals can also personalize their postcards to make their greetings more special.

With that said, the Nengajyo has slowly become less appealing to today’s Japanese youth. According to Japanese Youtuber Shogo, as well as many other sources, the act of sending postcards is considered to be an old-school tradition, especially since smartphones and computers exist. But, of course, it is still a tradition that is very much alive and done by the older Japanese generations.

The First Sunrise

On the first day of the year, the Japanese wake up early to gaze upon the beautiful sunrise. The first sunrise of the year is called the “Hatsuhinode.”

It is said that during Hatsuhinode, Toshigami-sama will descend from the heavens into the earth. The Japanese gather to witness the New Year’s sunrise’s beauty and honor the coming of Toshigami-sama.

This Japanese New Year tradition is said to have originated during the Meiji Period. The “shihohai,” which was the Japanese Imperial New Year’s Ceremony, slowly spread to normal people and naturally developed into today’s modern-day tradition.

Japanese residents and tourists can experience Japan’s First Sunrise in many different places. Some popular spots include Tokyo Skytree, Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, Mt. Takao, and Mt. Mitsutoge.

Money Gifts

The tradition of parents or adults giving money to children during the New Year is called “Otoshidama.” It is considered the second part of Christmas since children will receive more presents.

Many Japanese individuals believe that this tradition has deep roots in Japanese folklore. They believe that giving money to children is equivalent to giving offers to Toshigami-sama. In return for their offerings, Toshigami-sama serves as the protector of the children.

Giving money or gifts to children started during the Edo Period (1603-1868). During this era, wealthy families, businesses, and individuals started giving out mochi to families to celebrate the New Year. This explains the “dama” component of Otoshidama, as when written in kanji, it is written as “お年玉” – literally the kanji for year, and the kanji for ball.

Eventually, the tradition centered on specifically giving mochi to children, and during Japan’s economic growth in the 1950s and 1970s, it is assumed that adults started giving money to children instead of mochi. When this started happening, they started giving the money inside little envelopes so it could seem more present-like and more visually appealing than just handing over some cash.

Like the Japanese New Year post cards, these Japanese New Year envelopes can be bought in all kinds of designs, featuring generic New Year themes, as well as famous and popular characters, especially as the recipients tend to be children.

Shop Otoshidama Envelopes Now!

In terms of how much money is given, there are no specific rules. There are, however, some rough guidelines. For instance, preschoolers receive 2,000 yen, while elementary and high school students get higher amounts, such as 3,000 or 5,000 yen.

In addition, depending on the adult’s relationship with the child, the amount can go higher. Children who are too young to appreciate money are given toys.

In terms of how Otoshidama is spent, it depends on the household. Some households set aside the money and only allow small portions to be spent. Others allow their children to spend their Otoshidama on expensive items they have wanted all year long.

Osouji

The term “osoji” translates to cleaning. Families gather to clean their houses during the New Year’s season and before “Omisoka,” or New Year’s Eve. This act is done to start the year with a clean state. Japanese families also take this opportunity to set up their traditional Japanese decorations. This is similar to the Western tradition of “Spring Cleaning”.

Create a free ZenMarket account now.

Visiting Shrines and Temples

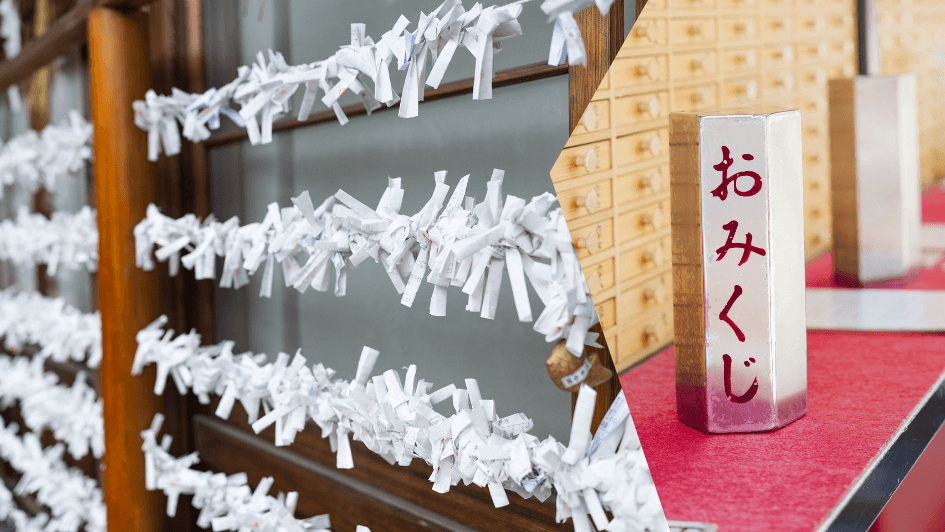

Japanese families visit shrines and temples during the first three days of the year. This Japanese New Year tradition is called “Hatsumode.”

The purpose of this tradition is for the Japanese people to express gratitude for the previous year and to pray for good fortune. During their visits, the Japanese buy new “omamori” or charms to ward off evil spirits. In fact, the word mamori means “to protect”. For foreigners visiting Japan, Omamori make great souvenirs.

In Japan, the omamori’s power is regarded to weaken after one year, so when a new one is purchased, their old ones are returned to be cremated.

While at the shrine, Japanese people also buy “omikuji” or fortune-telling paper strips to see what their luck will be like for the New Year. Fortunes that predict good luck or “dai-kichi” (大吉), and fortunes that predict regular luck or “chuu-kichi” (中吉), are typically tied to fences or hanging racks at the temple they were purchased.

On the other hand, fortunes that predict bad luck or “kyou” (凶) are usually burnt to purify the person as best they can. You will often see young people who go together making fun of eachother for getting the bad luck prediction.

Young people often do these omikuji, but the fortune is usually taken with a grain of salt and is all in good fun. It is treated more as a bit of fun. Some older folk take the fortune very seriously however.

People also often write their wishes for the New Year on wooden plates called “ema.” In recent years, lines in shrines and temples are usually long, and foreigners can also take part in the fun.

Japanese families keep a positive atmosphere and continue to conduct this tradition, despite it being somewhat old fashioned. During their first visit to Japanese shrines and temples, Japanese families often wear traditional kimono instead of their usual western-style clothes.

Also Read: HOW MUCH DOES A KIMONO COST: [PRICE, STORES, ACCESSORIES]

Traditional Japanese New Year Food

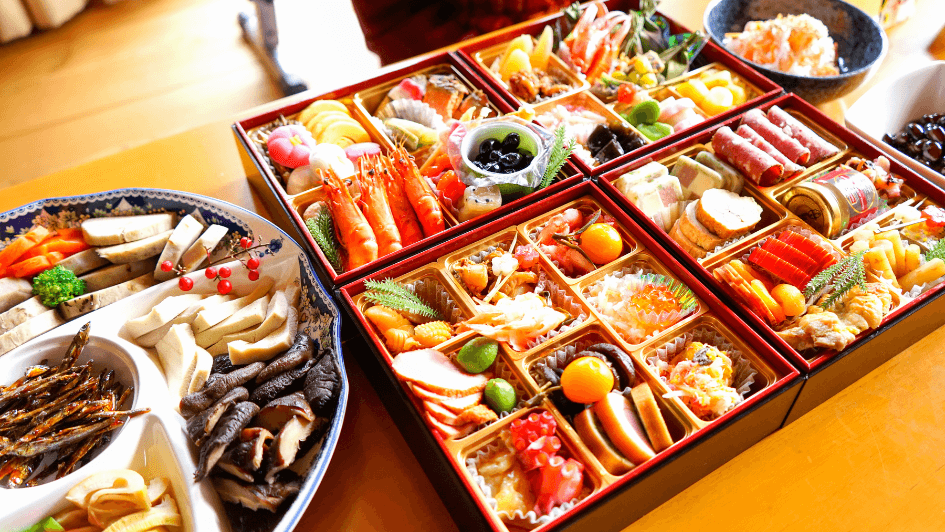

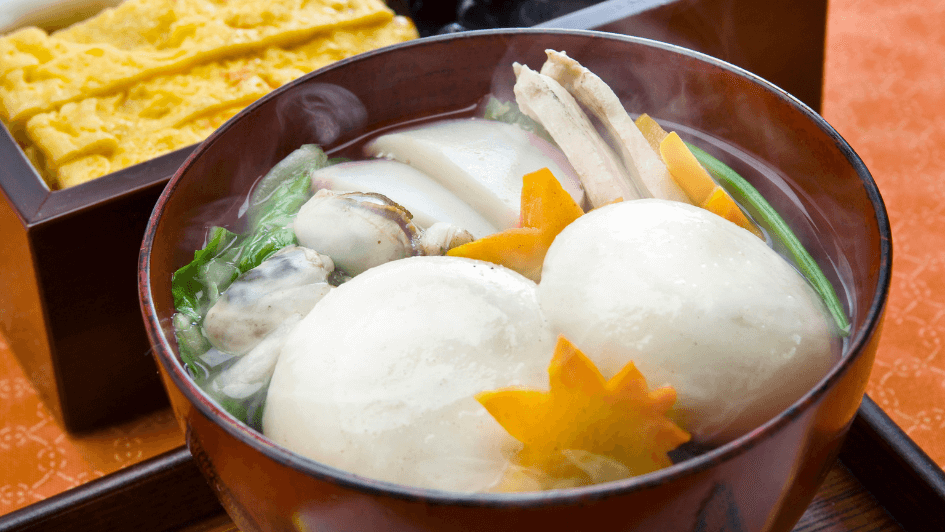

Two traditional Japanese foods are considered essential during the New Year’s celebrations. These are the “Osechi” and the “Ozoni.”

Osechi is a Japanese New Year’s dish that symbolizes prosperity and luck. There is a huge variety of over 20 to 30 different types. Each ingredient in the Osechi has a special meaning. Even the packaging, which is a stacked multi-layered box that resembles a giant obento, represents overlapping happiness.

Ozoni, on the other hand, is a Japanese soup using mochi, radish, carrots, and leek. The mochi in the Ozoni is dedicated to Toshigami-sama. It is made using the first water and fire of the year. Just like the Osechi, the ingredients, shape, and flavor of the Ozoni vary depending on the region.

Japanese mandarins, mikan (みかん), are also in season at this time of year. They make for a cheap and juicy snack for children and adults alike. They are typically eaten in between the main meals througout the day.

As for drinks, the Japanese tend to drink Otoso (お屠蘇), which roughly translates to New Year’s sake. However, this drink has a deeper meaning. A part of its name is believed to be the name of a demon. Hence, drinking Otoso cleanses the body of evil spirits.

The cups and pourers are quite unique and have beautiful designs. The are perfect for enjoying sake in the cold Winter months to help warm up your body.

The Heian nobility imported the tradition of drinking Otoso from China’s Tang Dynasty. It eventually made its way to commoners during the Edo period.

During the New Year, families drink Otoso starting with the youngest person and ending with the oldest person. Drinking it in this order allows the eldest member of the family to absorb the strength and energy of the younger members.

Oshogatsu Media & Pop Culture

Because families are all together and typically at home over New Year’s in Japan, media companies and TV broadcasters see it as a great opportunity to put on many amazing New Year’s specials. Prior to television arriving in Japan, the same opportunities were seen by radio broadcasters.

Japanese New Year/Oshogatsu Song

During Japan’s year-end celebration, the song “Haru no Umi” ((春の海) is played in shops, restaurants, TV, radio stations, and many more. The song translates to “Spring Sea” and is composed by famous Japanese composer Michio Miyagi.

The song uses koto (箏), a traditional Japanese stringed instrument, and shakuhachi (尺八), a traditional Japanese bamboo flute. Many Japanese residents feel a deep spiritual connection with this song, and it is a universally loved Japanese piece.

It should also be noted that Hotaru no Hikari, Japan’s version of Auld Lang Syne, is used as a symbol of closing, and while it can be heard at stores throughout the year, it is used during Oshougatsu to symbolise the year coming to a close.

Japanese New Year TV specials

In Japan, there are two major programs that are particularly popular for families to watch during New Year’s.

Kouhaku Uta Gassen

Kouhaku Uta Gassen, often referred to simply as Kouhaku, is a music program featuring a number of artists that gained popularity in the previous year, as well as older acts that have been well known in Japan for some time.

Throughout the show, two teams of artists perform acts against each other to earn a score for their team, with a winning team being announced just before the New Year countdown.

Once a winner is decided, all participants join in singing Hotaru no Hikari.

The show began on radio in the early 50s and continued on TV until the present day.

Kouhaku has seen hundreds of popular Japanese artists throughout this time. Some Kouhaku regulars include:

- Aki Yashiro

- Akiko Wada

- Akira Fuse

- Ayako Fuji

- Chiyoko Shimakura

- Frank Nagai

- Harumi Miyako

- Haruo Minami (equal 1st with 50 appearances)

- Hideo Murata

- Hiromi Go

- Hiroshi Itsuki

- Ichiro Toba

- Kaori Mizumori

- Kenichi Mikawa

- Kiyoko Suizenji

- Miyuki Kawanaka

- Natsuko Godai

- Saburo Kitajima (equal 1st with 50 appearances)

- Sachiko Kobayashi

- Sayuri Ishikawa

- Seiko Matsuda

- Shinichi Mori

- SMAP

- Takashi Hosokawa

- Yoshimi Tendo

Amazingly, the above have appeared on Kouhaku over 20 times each.

Other popular acts such as Arashi, Masaharu Fukuyama, AKB48, L’Arc-en-Ciel, Exlie, Namie Amuro, and many more. The list goes on and on.

Check out some of their albums to hear some music that Japanese people of all ages love.

Also Read: HOW TO BUY VINYL RECORDS FROM JAPAN?

An interesting part of this program is that it does not just feature Japanese artists, but also foreign artists that have a fandom in Japan.

Cyndi Lauper appearing on Kouhaku Japan, 1990

Notable acts that have competed include:

- BoA

- Cho Yong-Pil

- Chris Hart

- Cyndi Lauper

- Paul Simon (of Simon & Garfunkel)

- The Ventures

- TVXQ

- Twice

- Kye Eun-sook

Check out Japanese CDs of these foreign acts. Alternatively, check out Kouhaku on DVD or Blu-Ray.

Gaki no Tsukai ya Arahende Zettai ni Waratte ha Ikenai (You Must Not Laugh)

Kansai in particular is famous for its comedy acts and there are none more well known than Downtown, the manzai duo made up of Hitoshi Matsumoto and Masatoshi Hamada. When this duo joined forces with other famous comedy acts Cocorico, made up of Naoki Tanaka and Shozo Endo, and comedian and rakugo speaker Tsukitei Hosei, they formed Gaki no Tsukai.

The group runs many comedy specials throughout the year, including no laughing specials. In the no laughing specials, the group are are asked to perform challenges, and if they laugh they will receive some kind of punishment.

For the New Year Absolutely No Laughing special, this challenge goes for an entire day, and features many recurring characters and tropes.

Each year, the Gaki no Tsukai boys are assigned uniforms or costumes to fit around a certain theme, and ride a bus to a nearby school that has been decorated based on the theme of the year. The comedy begins from the moment they get on the bus. From this point on, if any of them laugh, a person wearing a camouflage suit and black balaclava will come and smack the person who laughed on the butt.

The main challenge is that the team are subjected to the comedy stylings of many of Japan’s top comedy acts in combination with cameo appearances from Japanese celebrities from all industries. The subject matter of the jokes ranges from simple potty humor, to real life scandals the cast have been involved in, to elaborate pranks, games and over-the-top performances.

Some regular acts on the New Year’s Zettai ni Waratte ha Ikenai special include:

- Chidori, a popular manzai act featuring Daigo (Daigo Yamamoto), and Nobu (Nobuyuki Hayakawa).

- Heipo (Toshihide Saito)

- Hackam Naronpat (Thai-Kick)

- Masahiro Chono (Chono)

- Cookie (Kunihiro Kawashima)

To say that what goes on is chaos would be an understatement. It is a wonder that some of the things even go to air. See below a clip of some of the lengths that they get up to in order to make the crew laugh and receive their punishment.

Japanese New Year Fireworks

As mentioned earlier, fireworks aren’t a part of Japan’s traditional New Year’s celebration, but certain areas do have fireworks displays for foreigners who wish to celebrate the New Year in Japan, or for those who simply want to watch fireworks.

In other words, fireworks are slowly becoming a feature of modern New Year’s in Japan.

The most popular areas for New Year fireworks displays include Tokyo Disney Land and Hakkeijima Sea Paradise in Yokohama.

New Year’s / Oshougatsu Shopping

In welcoming the New Year, families spend time together, which causes them to think about the time they spend together and what the New Year will bring. This ecourages people to buy things for those they love, their household or even for themselves to complete their New Year’s resolutions.

Retailers recognized this, and chose the New Year holiday to put on all kinds of sales, similar to what is seen on Black Friday in Western countries, minus the pushing and shoving (usually).

New Year’s Day is the biggest shopping day of the year in Japan. The sheer business of shopping malls in combination with the fact that many non-retail workers are on holiday puts massive strain on Japanese logistical and transport networks.

Imagine if Black Friday or Boxing Day occurred on Christmas Day. That’s the kind of event you are looking at. As you could imagine, the delivery of online orders is slowed in this time as staff scramble together to serve customers in-store.

If you order anything online during this period, expect an extra delivery day (or three) on top of what is written on the website.

Also Read: THE IMPACT OF JAPAN’S NEW YEAR HOLIDAYS ON ZENMARKET ORDERS

New Year Lucky Bags

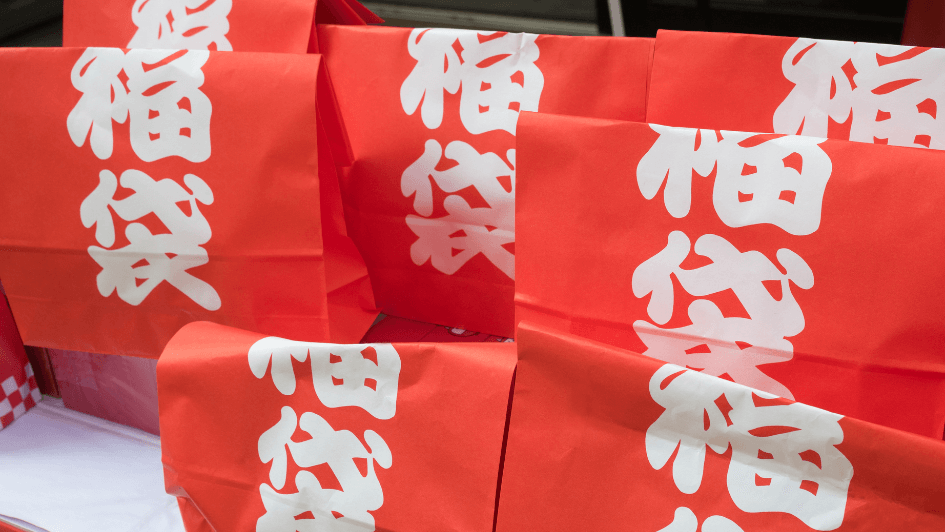

One of the most anticipated special products during Japan’s New Year is the “Fukubukuro” or New Year lucky bag. In a nutshell, a Fukubukuro is a special sealed bag containing several different items. In many ways, it is similar to a “mystery box.”

However, what sets Japanese lucky bags apart is that they are guaranteed to contain items of higher value than the price of the lucky bag. So essentially, lucky bags offer great value and aren’t just a waste of money.

Also Read: HOW TO BUY LUCKY BAGS (FUKUBUKURO) FROM JAPAN

The Ginza Matsuya Department Store introduced the Fukubukuro during the late Meiji era, and since then, the concept has been adopted by many stores throughout Japan. Today, everything from clothing shops to specialized hobby and toy stores offers Fukubukuro.

Some popular stores known for offering Fukubukuro include Amazon Japan, Rakuten Japan, Kate Spade, A Bathing Ape, Zooland, Disney Japan, Adidas Japan, E-earphone Japan, Sound House Japan, and many more.

Also Read: HOW TO BUY FROM AMAZON JAPAN | AMAZON JAPAN SHOPPING GUIDE

Also Read: HOW TO BUY FROM RAKUTEN JAPAN: A COMPLETE GUIDE

Also Read: HOW TO BUY BAPE FROM JAPAN (STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE)

Also Read: HOW TO BUY FROM DISNEY JAPAN [STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE]

How do you say Happy New Year in Japanese?

There are many ways to say Happy New Year in Japan. Some of the most common phrases include “Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu” (明けましておめでとうございます), “Shinnen omedeto gozaimasu” (新年おめでとうございます), and “Kinga Shinnen” (謹賀新年).

Other variations include “yoi otoshi wo omukaekudasai” (良いお年をお迎えください), which roughly translates to “Have a good year.” It is used before January 1st. And once New Year arrives, the phrase “Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu” replaces it. It is often shortened simply to “yoi otoshi wo”.

“Kotoshimo yoroshiku onegai shimasu” (今年もよろしくお願いします) is also usually added to signify gratitude. Lastly, “Ake ome! Koto yoro!” (あけおめ! ことよろ !) is a shorter version of “Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu” used casually by friends and children.

Japanese people also tend to add phrases to their New Year’s greetings. A common one is “Sakunen wa o-sewa ni narimashita” (昨年はお世話になりました) which translates to “Thank you for all your support last year.”

These Japanese New Year greetings are an essential part of Japanese culture. Japanese Families emphasize that younger members of the family should genuinely give these greetings to relatives and colleagues. These greetings allow individuals to maintain a good relationship with each other and symbolize maturity within the Japanese community.

How do you say New Year’s Resolution in Japanese?

New Year’s resolution in Japan is known as “Shinnen no hōfu” (新年の抱負). Like the rest of the world, the Japanese set new goals and aim to change bad habits for the coming year. Here are some common Japanese New Year’s resolutions:

- “Hon o takusan yomu.” (本をたくさん読む) – Read a lot of books

- “Kazoku to ōku no jikan o sugosu” (家族と多くの時間を過ごす) – Spend more time with family

- “Yaseru” (やせる) – Lose weight

- “O-kane o tameru” (お金を貯める) – Save money

- “Kin’ensuru” (禁煙する) – Quit smoking

- “Naraigoto o hajimeru” (習い事を始める) – Learn something new

- “O-sake no ryō o herasu” (お酒の量を減らす) – Drink less

- “Undō no shūkan o minitsukeru” (運動の習慣を身につける) – Start an excercise routine

- “Kenkō-teki na shokuseikatsu o kokorogakeru” (健康的な食生活を心がける) – Eat healthy

[ad_2]

Source link