[ad_1]

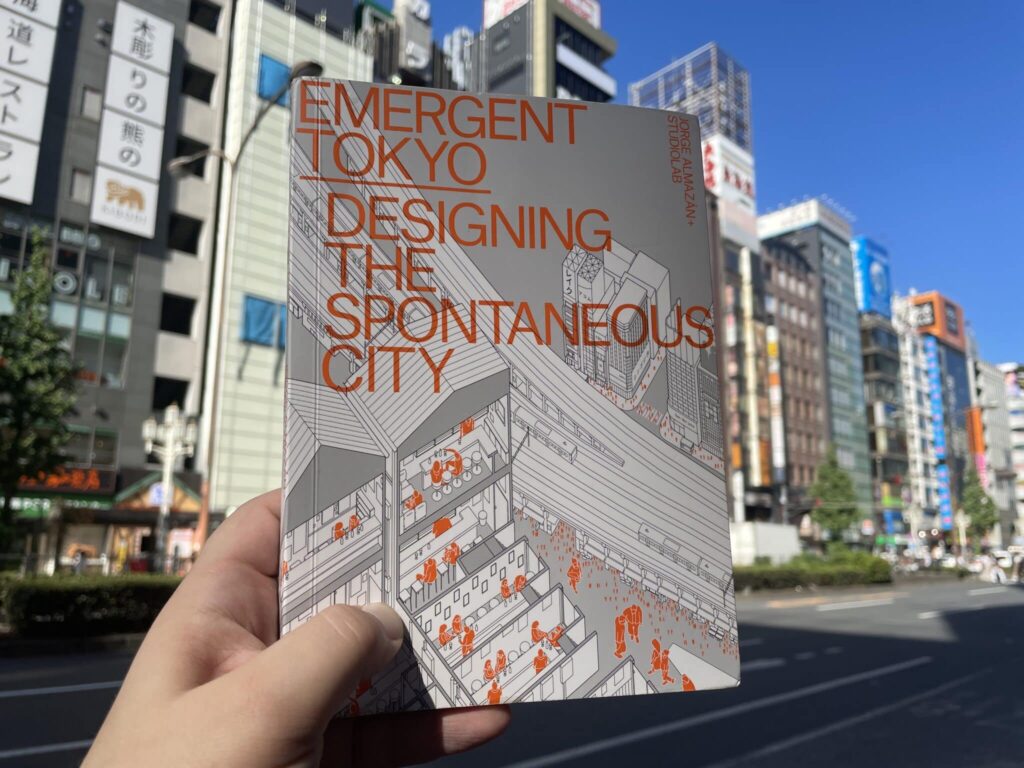

Twilight was coming on as I walked through the narrow alleyways of Shibuya’s diminutive Nonbei Yokocho neighborhood. Despite over a decade of visiting Shibuya for the usual carousing and shopping, I’d somehow missed the yokocho‘s existence; something that has only become easier as Shibuya has been built up, massive highrises obscuring even more of its environs. As the book then in my backpack describes, the block of minuscule bars “sits relatively unnoticed between giant modern skyscrapers, a pocket of life in the midst of the global city.” Somehow, it’d taken reading ‘Emergent Tokyo‘ to introduce me to one of the city’s coolest backstreets.

The backstreets in question are one of many distinctive yokocho neighborhoods scattered across Tokyo. Yokocho (横丁) are narrow, semi-hidden alleyways filled with bars and restaurants; they often carry a feeling of old Tokyo, like something out of the early postwar era. That makes sense, since many of the most famous yokocho emerged from the black markets that crowded around major train stations in the wake of the devastation of WWII. Shinjuku’s now-internationally famous Golden Gai is an especially prominent yokocho; Nonbei Yokocho (“Drunkard’s Alley”) is smaller, both in terms of overall footprint and bar size.

I was with two friends, none of us strangers to Shibuya, but all first-timers to Nonbei. We managed to grab three of the roughly six seats available at Bar Usagi. The tiny space, intimate in the extreme, felt familiar; that would be because ‘Emergent Tokyo’ happens to feature a detailed cross-section of the bar. We got some beers, raised our glasses in the standard kanpai, and enjoyed the cozy ambiance of a space only 4.8m2 wide – and yet representative of one of the urban phenomena that make Tokyo such an incredibly alluring city.

Tokyo Emerges

I’ve lived in Tokyo for years; for even longer, Tokyo was a central location visited on weekends while I was working in Japan’s distant rural spaces. I’ve always loved this city, ever since I first briefly set foot in it as a fresh-faced high school exchange student in 2006. While the sheer size and clamor of Tokyo can overwhelm, for many, visitors or residents, Tokyo holds an almost unmatchable charm. And if you’re looking to understand more of this city – how it came to be, how it functions, what makes it unique – and where it may heading – it would be hard to find better reading material than ‘Emergent Tokyo’.

The book is equally fascinating from an academic and a touristic perspective. Are you an old hand to Tokyo, interested in learning more about its zoning and right-to-light laws? Great, you should read it. New to Tokyo, and hoping to have a deeper understanding of the iconic sights in Kabuki-cho and Shibuya? You’re also in luck! ‘Emergent Tokyo’ is both approachable and scholarly. It manages to do all this within a framework that both highlights Tokyo’s strengths as a city without essentializing or, worse, exoticizing.

The Seven Tokyos

‘Emergent Tokyo’ tackles the massive physical diversity of the megacity by breaking it down into component archetypes. These seven neighborhood types will be instantly recognizable for those who have spent time in Tokyo. Village, Local, Pocket, Mercantile Yamanote, Mercantile Shitamachi, Mass Residential, and Office Tower; each is defined and mapped out based on the chome blocks designated by each Tokyo Ward. The authors acknowledge the porous nature of these divisions, and set out what makes them unique – all while attempting to avoid hierarchies. “There is a different Tokyo for every season,” say the authors in the introduction. “Even the most humdrum neighborhoods can evolve in new directions over time.”

Amongst these divisions are found “urban patterns” that typify what makes Tokyo special. Describing and enumerating these unique features of the city takes up the majority of the book. These are the aforementioned yokocho; recognizable Zakkyo buildings, narrow rectangles where each floor hosts a different business; Undertrack infills, where the space underneath raised train tracks and highways take on a vibrant urban life; Ankyo streets, filled-in rivers and canals that help trace the old features of Meiji Tokyo and the feudal Edo before it; and, lastly, the dense low-rise neighborhoods that so many Tokyoites call home.

The book provides case studies for each of these urban patterns. For yokocho, we learn about ever-popular Golden Gai, the tiny drinking spaces of Nonbei Yokocho, and the al fresco bars of Yanagi Koji in Nishi-Ogikubo. Detailed but aesthetically pleasing graphs, diagrams, and maps abound in each section. Readers may find themselves pouring over the visuals for almost as much time as they spend reading.

Theorizing Tokyo

‘Emergent Tokyo’ does more than simply indulge the sheer interest inherent in delving into each of these Tokyo phenomena. Instead, the book examines what exactly it is that makes Tokyo so, well, Tokyo. Central here is the concept of ’emergence.’

What, exactly is emergence? The book offers the unified behavior of large flocks of birds as an example. “This is not the result of a leading bird somehow transmitting orders with a mysterious animal telepathy; the flock’s coherent behavior simply emerges from each bird responding to the movements of its neighbors.”

The book posits that Tokyo, too, functions in this way. Historical events – the war, the postwar economic boom – create rippling changes. Neighborhoods are built on the patterns of the rice patties and canals that once dotted the land underneath them. Beaurocracy and commerce have their say. But on the micro-scale, people are still making their own decisions.

High and Low in Tokyo

Take, for example, the dense housing on the island of Tsukishima, in Tokyo Bay. An artificial island, perhaps best known for its street of monjyayaki restaurants, Tsukishima fits a surprising amount of Tokyo archetypes and trends inside of its small footprint. Narrow alleyways separate rows of low single-family houses, their concrete covered in greenery. These tiny roji streets allow for “an extension of the domestic space.” Housing melds naturalistically with small commercial enterprises.

Look skyward, however, and one sees the giant high-rise apartment blocks that epitomize modern urban building trends – a common sight all around Tokyo Bay. In fact, the government aims to keep building more of these thousand-family structures in Tsukishima. The older dense residential neighborhoods are too dense, and seen as a fire hazard in case of earthquakes. Macro trends and local decision making are part of what makes these neighborhoods what they are.

Going Behind the Scenes

All this detail and insight makes ‘Emergent Tokyo’ required reading for anyone captivated by Japan’s capital city. On my own bookshelf, it’s already taken pride of place next to other classics of accessible Tokyology, like Seidensticker’s seminal “Low City, High City: Tokyo from Edo to the Earthquake.”

Fascinated by the content of Emergent Tokyo as I was, I jumped at the opportunity to find out a little more about the background of the book. Co-author Joe McReynolds, one-third of the book’s editorial team alongside Jorge Almazan and Saito Naoki, was kind enough to give me a short interview. Hopefully, you find it as insightful as I did.

How did you become involved with the Almazán Architecture and Urban Studies Laboratory, and with the creation of this book in particular?

Joe: It’s the unlikeliest thing that’s ever happened to me, a journey spanning a decade! I spent the 2010s working as a national security analyst in DC and full of wanderlust, traveling the world as much as I could. Tokyo was always my favorite city in the world — this city of endless possibility, yet it seemed to function so differently than any other place I’d encountered. I dreamed of actually studying how Tokyo works, but I assumed that was an “in another life…” fantasy rather than a real possibility. I kept collecting Japanese-language writings on Tokyo over the years, in case I might have a use for them someday.

[Joe speaks Japanese and studied abroad in Japan, but his day job in DC focuses instead on China.]

One leap led to another. I befriended Japanese national security researchers, and they offered me a visiting defense fellowship in 2019. I used that visa to finally embark on the urban studies research I’d always dreamed of, applying my training as an intelligence analyst to a city instead of military matters. And for some of the corners of Tokyo’s cityscape I was investigating, I found out there was another researcher in town who’d been looking into the same issues: my co-author on Emergent Tokyo, Jorge Almazan. I asked him to grab a coffee in the summer of 2019, and it was like meeting your counterpart from an alternate universe. We had very similar lenses on the city, though coming from totally different perspectives — he’s a practicing architect and a PhD-ed academic.

Four years ago this month, Jorge invited me to join his urban studies laboratory at Keio University, and the rest is history. It honestly felt like Kamala Khan getting called up to the Avengers, having the chance to work with urban studies scholars I’d idolized for years! We spent the two years of the pandemic debating and sharpening every single sentence in Emergent Tokyo, and now we’re hard at work on its sequel together with the rest of the incredible Studiolab team.

What was it like working on Emergent Tokyo, and what was your role?

It was an absolute dream. For the book research, I had to immerse myself into both the penthouses and dives of Tokyo, so to speak. My goal was to intimately understand both the major players behind both its gleaming redevelopment projects and the myriad subcultures of the night city. It was also, on some days, a nightmare; I had given myself a one-year, one-time shot to pursue the pipe dream of a lifetime, so the stakes felt intense.

I was working 100-hour weeks in a field I have no formal training in, operating in a foreign language I had never used professionally before, without a real paycheck of any kind, to write something that I assumed three people at most would ever read. It was an insane thing to do, even if it all worked out somehow in the end. As for my role — Emergent Tokyo is first and foremost a group effort. Jorge and I wrote and refined the text together over the two years of the pandemic, with Saito Naoki filling the book with beautiful graphics. We were backed up by over a dozen Studiolab graduate students and architects who carried out field research and case studies. The end result is, I believe, a far better book than any single one of us could have made on our own.

What is an area of Tokyo that you find particularly fascinating or enjoyable to spend time in?

The areas I love most in Tokyo are its intimate little communities, which often exist right in the shadow of megacity developments. Drunkard’s Alley (Nonbei Yokocho) and the Dogenzaka hill in Shibuya, where old-time postwar grit juts up against the shiny new corporate towers. Arakicho, the former geisha district turned ‘snack pub’ haven, in the heart of Shinjuku. Kyojima, one of Tokyo’s last century-old cityscapes and an old-school ‘low city’ (shitamachi) neighborhood of the highest order, where a new generation of DIY young artists is now making it their own. Omoide Nukemichi in Kabukicho, with its two-seat bars in back-alley shacks. The used bookstores of Jimbocho. I could go on and on. God, I love this city.

What makes you most worried about Tokyo’s future, and most hopeful?

I worry for Tokyo’s future when I hop into the redeveloped sections of the city that feel as if they could just as easily be in any capital city anywhere in the world. The Odaibas and the like. Overall I’m less worried about that future than you might think; property rights are so strong in Japan that you can’t really bulldoze over individual landowners unless they decide to sell, and Tokyo itself is so vast. But I foresee those corporate redevelopments growing, and I don’t love it.

As for what makes me most hopeful about Tokyo, it’s tempting to say ‘the people’, isn’t it? After all, Tokyoites are an endlessly creative and resourceful bunch. But the core message of our book is that Tokyo’s genius isn’t down to the unique personal qualities of Tokyoites, or of Japanese culture more broadly — people are people, and practical, concrete factors change how people interact with their cities.

So I’ll say that Japan’s friendly zoning rules give me hope. Japanese zoning is a big part of why Tokyo is — and will remain — a city with a near-limitless supply of ‘micro-spaces.’ These are the sort of places you can put a tiny bar or restaurant or boutique and have it not just be a place of commerce, but also a place for intimate social community at human scale; the sort of place where a person can feel genuinely known and seen. As long as Tokyo doesn’t lose that secret sauce, it’ll remain the world’s most fascinating city.

What to Read Next

[ad_2]

Source link