[ad_1]

July 25th, 2023, at sunrise. A cloudless sky hangs above Tokyo.

Before the sun begins to microwave the city in the baking heat, its reflection shimmers gently on the mossy green moat encompassing the Imperial Palace. As the daylight advances westward towards the great lakes of Mt. Fuji, colors of gold begin to dance on every body of water.

On a low bridge overlooking Shimizu Harbor in the seaside town of Yokosuna, you see rustic cranes and fishing boats. Sunlight flickers on the harbor’s small wrinkly waves.

Your senses turn to the mechanical sounds from the train track behind you.

Beyond those tracks, 57 years ago, the Hashimoto family should also have woken up to a sunrise like this. Instead, the final light cast over their skin was from the flickering flames that had just burned down their entire home––and lives.

It was June 30th, 1966, at 2:30 AM. The fire was out. Four people died.

But their case never did.

“He thinks the trial is over”

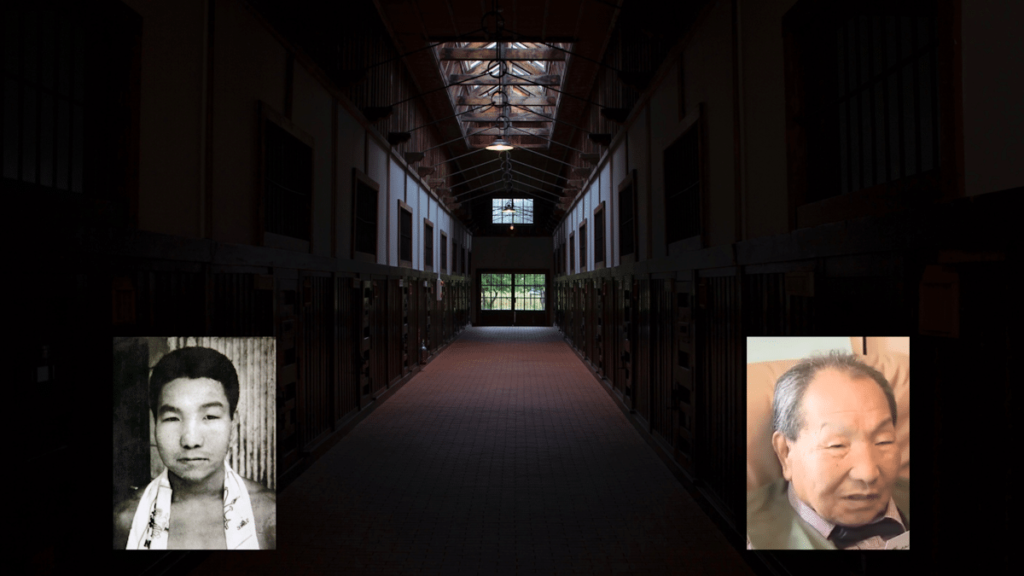

The Hashimoto family’s tragedy is better known as the Hakamada Incident. It’s named after Iwao Hakamada, now age 87–––the man who allegedly stabbed the four to death before setting fire to the Hashimoto home.

The Hakamada Incident has made Iwao Hakamada the world’s longest-serving death row inmate, certified by the Guinness world record.

55 years and counting since Iwao’s sentencing, he still has the Japanese justice system’s noose wrapped around his neck.

But evidence suggests that no noose belongs on Iwao’s neck. That the Japanese justice system made an innocent man waste away in a prison cell for 47 years.

“He lives in a delusion now. He thinks the trial is over,” says Hideko Hakamada, Iwao’s sister.

It’s been more than four decades in confinement. His calls for a non-guilty plea have gone unanswered. Iwao is now mentally impaired, incapable of grasping reality. Fighting on his behalf, Hideko and defense attorney Hideyo Ogawa are preparing for an upcoming retrial expected to commence later this year at Shizuoka District Court.

Unseen Japan joined a press conference today at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan (FCCJ) in Tokyo where Hideko and Ogawa addressed the latest developments in the case.

Corruption

Iwao fit the suspect’s profile conjured by police at the time.

Iwao was an employee of the Hashimoto family’s miso manufacturing company and lived in the worker’s dormitory located on the factory’s second floor. This would have given Iwao insider access to the company’s building where the Hashimoto family lived–––and died.

Forensics found the victims’ bodies covered with cuts and their clothes covered in gasoline, which had been used to start the fire. The police looked at Iwao for clues again. He had an injured left middle finger. They found pajamas with blood that wasn’t Iwao’s in his dorm room.

Police dug into Iwao’s past. He used to be a professional boxer. So, they figured, he’s capable of harm.

Police arrested Iwao in August of 1966, two months after the Hashimoto family’s death. Police held Iwao for approximately twenty days and interrogated him every day for ten to twelve hours.

Time was running out. The police had only three days left to force a confession out of Iwao. After that, they’d have to release him.

Forced confessions

On his twenty-first day of grilling questioning, Iwao confessed.

But the police wanted more. The police reaped forty-five confession documents out of the interrogations that followed.

The Japanese constitution clearly states that forced confessions are inadmissible in court and that confessions alone do not determine a guilty verdict. Most of Iwao’s confessions were thrown out of court. But then the police found a piece, or rather, five pieces of red, blood-soaked clothing at the bottom of a miso tank–––a year and two months after the incident.

“We have scientific proof that if blood-stained clothing sits in miso for a year and two months that the color becomes black,” says attorney Ogawa.

Ogawa and Hideko say they are certain that the police planted the five garments so that they could pin the crime on Iwao.

“Police knew that Hakamada was not guilty but planted evidence that would point the finger away from the real criminal,” says Ogawa at the FCCJ press conference.

According to Ogawa, the clothes belonged to whichever officer framed Iwao.

DNA tests corrupted?

Additionally, DNA tests have proven that the blood soaking the garments is neither Iwao’s nor the victims. The blood is not even from a Japanese.

“At the time in Japan, baiketsu (売血; blood-selling) was a big thing,” says Ogawa.

Ogawa claims that it was easy to get foreign blood around 1966. Further, he says the blood found on the five items of clothing had a DNA sequence rarely found in Japanese people. Ergo, the police must have made a purchase from the blood trade.

The DNA test contradicting the prosecution’s case didn’t matter to the Tokyo High Court, though. It cited how unreliable the DNA test was due to the possibility that the garments had been contaminated. It dismissed the defense’s counterevidence.

Forced confessions, planted evidence, and an inefficient justice system are what Hideko and Ogawa have been fighting, unbeknownst to the now-impaired Iwao himself.

Still fighting

Iwao has pled not guilty in every courtroom he appeared. Despite his efforts, the Shizuoka District Court served him the death penalty in September of 1968.

55 years later, Iwao is still alive and well. He’s not even in prison. But how?

Between his sentencing in 1968 and four decades later in 2008, Iwao appealed twice and filed for retrials three times.

Every attempt failed. But it kept him alive.

In 2008 Hideko demanded a retrial at the Shizuoka District Court. The court approved Iwao’s retrial in 2014 and suspended his death sentence. Since then, Iwao has been free from prison.

The Tokyo High Court reversed the 2014 approval for retrial after prosecutors appealed against it. This blocked Iwao’s chance at clearing his name. However, it didn’t affect his release from prison. Taking into consideration his old age, 82, the Tokyo High Court decided to keep Iwao on release and leave the suspension of his death sentence unchanged.

In December 2020, the Supreme Court revoked the 2014 Tokyo High Court’s reversal. Iwao’s retrial was back on track.

On March 13th this year, the Tokyo High Court approved a retrial for Iwao’s case citing faulty evidence that brings previous verdicts into question, referring to the five pieces of clothing.

The retrial will be held at Shizuoka District Court.

Two months later, Iwao made a public appearance at the Citizen’s Assembly for Revising Laws For Retrials (再審法改正をめざす市民の会の集会) held in Tokyo on May 19th where he met the former Shizuoka District Court judge Hiroaki Murayama who delivered the 2014 verdict.

Prosecutors push on

This month on July 10th, prosecutors announced plans to address the issues of submitted evidence via new investigations as they continue to build a case against Iwao.

“It is what it is. Nothing can be done, except for winning in court,” says Hideko.

On July 19th, Iwao’s defense team, the prosecution, and the Shizuoka District Court held their fourth pre-trial meeting. The defense requested the Shizuoka District Court to commence retrials this September to which the court said that “due to security issues we cannot decide on a date so quickly.”

At the same meeting, both the defense and prosecution confirmed that they are nearly done with collecting evidence. The prosecution plans to present 245 pieces of evidence including 16 new ones. The defense has prepared 269 pieces of evidence.

Losing the game to save face

“The prosecution knows they can’t prove Iwao guilty anymore,” says Ogawa.

In the history of the Japanese justice system, all four death penalty cases that underwent a retrial were given a non-guilty verdict. Iwao’s upcoming retrial is the fifth which is expected to turn out the same.

So why is the prosecution still pursuing a guilty verdict when it knows it’s a losing game?

“They don’t want a guilty verdict. They want to disprove our claim that they fabricated evidence,” says Ogawa.

“There’s also the possibility that they are cynically stretching the trial out so that our senior plaintiffs pass away before the verdict is reached, or that the public loses interest,” Ogawa shares.

Ogawa points out the broader issue this case represents. Current legislation does not protect the right to a fair retrial for those who need it, like Iwao. He cites the lack of transparency as the main reason why it has taken so long for the defense team to discover the fabrication of evidence.

Iwao’s team is gearing up for what they hope is the final trial to clear an innocent man’s name.

What to read next

#MeToo in JET: One Woman’s 7-Year Battle Against Sexual Abuse

Sources

[1] 事件の概要袴田さん. 支援クラブ

[2]【ネット初掲載】鎌田慧の痛憤の現場を歩く「冤罪・袴田事件(上)」. 週刊金曜日オンライン

[3] ⒈放課現場から死体発見. 袴田事件弁護団

[4] 「袴田事件」ってどんな事件?/ 早稲田塾講師 坂本太郎のよくわかる時事用語. Yahoo! ニュースJapan

[5] 「袴田事件」死刑判決を受けていた袴田巌さんのやり直し裁判検察は有罪立証. TBS NEWS DIG

[6] 袴田巌さん再審へ事前協議 弁護団・検察の証拠ほぼ出そろう. NHK

[7] 袴田事件. 日本弁護士連合会

[8] 袴田事件の再審認めず、釈放は維持 東京高裁決定. 日本経済新聞

[9] 【袴田事件】袴田巌さん 釈放を決めた静岡地裁の元裁判長と初対面|TBS NEWS DIG. TBS NEWS DIG

[ad_2]

Source link